Last week, I wrote an article about the Repository pattern for Eloquent entities and show how useless it is, but I promised to tell how it can be used partially. To do this, I will try to analyze how this pattern is usually used in projects. The minimum required set of methods for the Eloquent repository:

interface PostRepository

{

public function getById($id): Post;

public function save(Post $post);

public function delete($id);

}

However, in real projects methods for entities fetching are often added to repository classes:

interface PostRepository

{

public function getById($id): Post;

public function save(Post $post);

public function delete($id);

public function getLastPosts();

public function getTopPosts();

public function getUserPosts($userId);

}

This functionality could be implemented by Eloquent scopes, but entity classes become too big in that case. So implementing it in repository classes looks logical. Is it? I've visually separated this interface into two parts. The first part of methods will be used in write operations.

Usual write operations are:

- constructing a new object and PostRepository::save call

- PostRepository::getById call, manipulations with entity and PostRepository::save call

- PostRepository::delete call

Entity fetching methods are not used in write operations. On the other hand, only get* methods are used in read operations (read operations only show some information, without changing the data, usually all HTTP GET are read, POST requests are write). If you have read about the Interface Segregation Principle (the I letter in SOLID), then it becomes clear that our interface became too large and took at least two different responsibilities. It's time to separate it into two. The getById method is required in both, but if the application becomes more complex, implementations will be different. I'll write about it a bit later. I already wrote why I don't like the write part in the previous article, so I’ll just forget about it in this one.

Read part seems to me not so useless, because even for Eloquent there may be several implementations. How to name a class? ReadPostRepository? But it's already not a repository. Just PostQueries?

interface PostQueries

{

public function getById($id): Post;

public function getLastPosts();

public function getTopPosts();

public function getUserPosts($userId);

}

It's Eloquent implementation is pretty simple:

final class EloquentPostQueries implements PostQueries

{

public function getById($id): Post

{

return Post::findOrFail($id);

}

/**

* @return Post[] | Collection

*/

public function getLastPosts()

{

return Post::orderBy('created_at', 'desc')

->limit(/*some limit*/)

->get();

}

/**

* @return Post[] | Collection

*/

public function getTopPosts()

{

return Post::orderBy('rating', 'desc')

->limit(/*some limit*/)

->get();

}

/**

* @param int $userId

* @return Post[] | Collection

*/

public function getUserPosts($userId)

{

return Post::whereUserId($userId)

->orderBy('created_at', 'desc')

->get();

}

}

This implementation should be bound to interface in provider:

final class AppServiceProvider extends ServiceProvider

{

public function register()

{

$this->app->bind(PostQueries::class,

EloquentPostQueries::class);

}

}

This class is already useful. It takes an entity selecting responsibility and removes this logic from controllers or entity classes. It can be used in controller like that:

final class PostsController extends Controller

{

public function lastPosts(PostQueries $postQueries)

{

return view('posts.last', [

'posts' => $postQueries->getLastPosts(),

]);

}

}

PostsController::lastPosts method asks PostsQueries interface implementation and works with it. PostQueries interface is bound with EloquentPostQueries class and controller will get its instance.

Let's imagine that our application has become very popular. Thousands of users per minute open a page with the latest publications. The most popular publications are also read very often. Databases don't like such loads, so developers usually use a standard solution to reduce the loading from database - a cache. Some hot data is stored in a storage optimized for massive read operations - memcached or redis. The caching logic is usually not so complicated, but implementing it in EloquentPostQueries is not very correct (just because of the Single Responsibility Principle). It is much more natural to use the Decorator pattern and implement caching as decoration for the main action:

use Illuminate\Contracts\Cache\Repository;

final class CachedPostQueries implements PostQueries

{

const LASTS_DURATION = 10;

/** @var PostQueries */

private $base;

/** @var Repository */

private $cache;

public function __construct(

PostQueries $base, Repository $cache)

{

$this->base = $base;

$this->cache = $cache;

}

/**

* @return Post[] | Collection

*/

public function getLastPosts()

{

return $this->cache->remember('last_posts',

self::LASTS_DURATION,

function(){

return $this->base->getLastPosts();

});

}

// other methods are almost the same

}

Don't pay much attention to the Repository interface in the constructor. For some reason, Laravel developers decided to call the interface for caching like that.

The CachedPostQueries class implements only caching. The $this->cache->remember call checks if this entry is in the cache and if not, calls the callback and writes the returned value to the cache. The last step - correctly register this class in our application. All application classes should get a CachedPostQueries instance if they ask PostQueries interface. However, CachedPostQueries itself should receive an EloquentPostQueries instance, since it cannot work without a "real" implementation. Changes in the AppServiceProvider:

final class AppServiceProvider extends ServiceProvider

{

public function register()

{

$this->app->bind(PostQueries::class,

CachedPostQueries::class);

$this->app->when(CachedPostQueries::class)

->needs(PostQueries::class)

->give(EloquentPostQueries::class);

}

}

All my wishes are quite naturally described in the provider. So, I've implemented caching for post queries only by writing one class and changing the configuration of Laravel's container. The rest of the application code wasn't changed.

Of course, for the full implementation of caching, cache invalidation also should be implemented. Deleted article should not hang on the site for some time after deleting. It should disappear immediately. But it's not this article's point (I wrote a special article about caching).

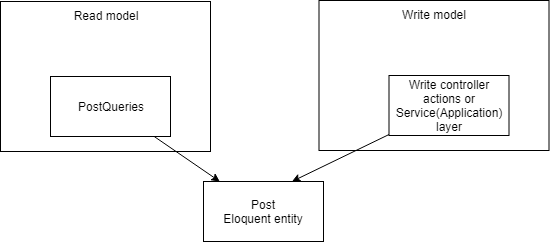

So, I used not one, but two patterns. The Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) pattern proposes to completely separate the read and write operations at the interface level. I came to him through the Interface segregation principle, which means that I skillfully manipulate with patterns and principles and derive one from the other as a theorem :) Of course, not every project needs such an abstraction on entities selecting, but I will share one trick with you. At the initial stage of application development, you can simply create a PostQueries class with usual Eloquent implementation:

final class PostQueries

{

public function getById($id): Post

{

return Post::findOrFail($id);

}

// Other methods

}

When caching need arises, you can easily create an interface (or abstract class) instead of this PostQueries class, copy its implementation to the EloquentPostQueries class and continue with the scheme I described earlier. The rest of the application code does not need to be changed.

However, this is not a true CQRS. Read and write operations uses the same Post entity.

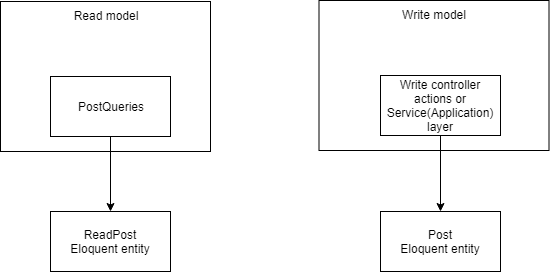

Someone can fetch Post entity from PostQueries, change it and save the changes to database be calling ->save(). This will work, but after some time application might start to use master-slave replication, for example and EloquentPostQueries will work with read replicas. Well-configured read replicas don't allow any write queries(INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE) so this code become to fail and team will spend a lot of time to fix that issue. There also a lots of other reasons to don't use cached Eloquent entities for write operations.

Obvious solution - separated read and write application parts totally. Team can continue to use Eloquent, by creating a class for read-entities, which protected for writing. Example: https://github.com/adelf/freelance-example/blob/master/app/ReadModels/ReadModel.php. Create a new model ReadPost for example (Post is also acceptable, but it should be moved to another namespace, because old Post class will be used for write operations):

final class ReadPost extends ReadModel

{

protected $table = 'posts';

}

interface PostQueries

{

public function getById($id): ReadPost;

}

Another option: remove Eloquent from the project. There are some reasons for that:

- All table fields are almost never needed. For lastPosts requests, only id, title and, for example, published_at fields are required. Fetching several heavy post text values will only give an unnecessary load on the database and cache. Eloquent can select only required fields, but this is very implicit. PostQueries clients don't know exactly which fields are selected, without looking into the implementation.

- Caching uses serialization by default. Eloquent classes are too large in serialized form. It is not noticeable for simple small entities, but it becomes a problem for large entities with many relations. On one of my projects, the usual class with public fields took 10 times less space in the cache than the Eloquent entity (there were many small sub-entities). It is possible to cache only attributes field, but this will complicate the cache process a lot.

A simple example of how this might look like:

final class PostHeader

{

public int $id;

public string $title;

public DateTime $publishedAt;

}

final class Post

{

public int $id;

public string $title;

public string $text;

public DateTime $publishedAt;

}

interface PostQueries

{

public function getById($id): Post;

/**

* @return PostHeader[]

*/

public function getLastPosts();

/**

* @return PostHeader[]

*/

public function getTopPosts();

/**

* @var int $userId

* @return PostHeader[]

*/

public function getUserPosts($userId);

}

I've used a new typed properties feature, which should be implemented in PHP 7.4.

Well, all this looks like an over-complication of logic. "Take the Eloquent scopes and everything will be fine. Why do you invent all this?". This is correct for simple projects. Absolutely no need to reinvent scopes there. But when a project is large and several developers are involved in development, which often change, the rules of the game become slightly different. It is necessary to write the code protected so the new developer could not do something wrong after a few years. It is, of course, impossible to completely eliminate such a probability, but it is necessary to reduce it.

In addition, this is the usual decomposition of the system. You can collect all caching decorators and classes for cache invalidation into a kind of "caching module" and remove it from the rest of application. Once I worked with complex queries surrounded by cache calls. It's not convenient, especially if caching logic is not as simple as described above.

All these tricks with classes, interfaces, Dependency Injection and CQRS are described in detail in my book "Architecture of complex web applications". There also an answer for the question "why all classes in examples to this article are marked as final?".